"Boo" Bubbles

There are many things that I do not excel at as a parent. That’s really true of life in general; everyone has things they are really good at and other things they don’t do so well. For example, I am really bad at pretending. Even as a child, I didn’t love playing with dolls and stuffed animals, or making my Barbies talk to each other. And to this day, I really don’t like getting down on the floor and playing those types of things with my kids. I used to think that not wanting to play with my kids made me a bad parent and that my children would seriously lack imagination if I didn’t play with them, but it actually doesn’t mean either of those things are true. Solo play is an important part of developing creative thinking, problem solving and attention span. To be fair, I love spending time with my kids, just not doing that. And I find that I make much more meaningful connections with them when we are all actively engaged in whatever it is we are doing. So, when it comes to certain types of pretend play, my kids are on their own and we find other activities that we enjoy doing together: reading books, playing board games, taking bike rides…

…doing science experiments. I don’t know if it’s that we all just love science, or that they love it because I do; either way we’re here for a good science experiment. And making these “boo bubbles” from Steve Spangler Science was a good one.

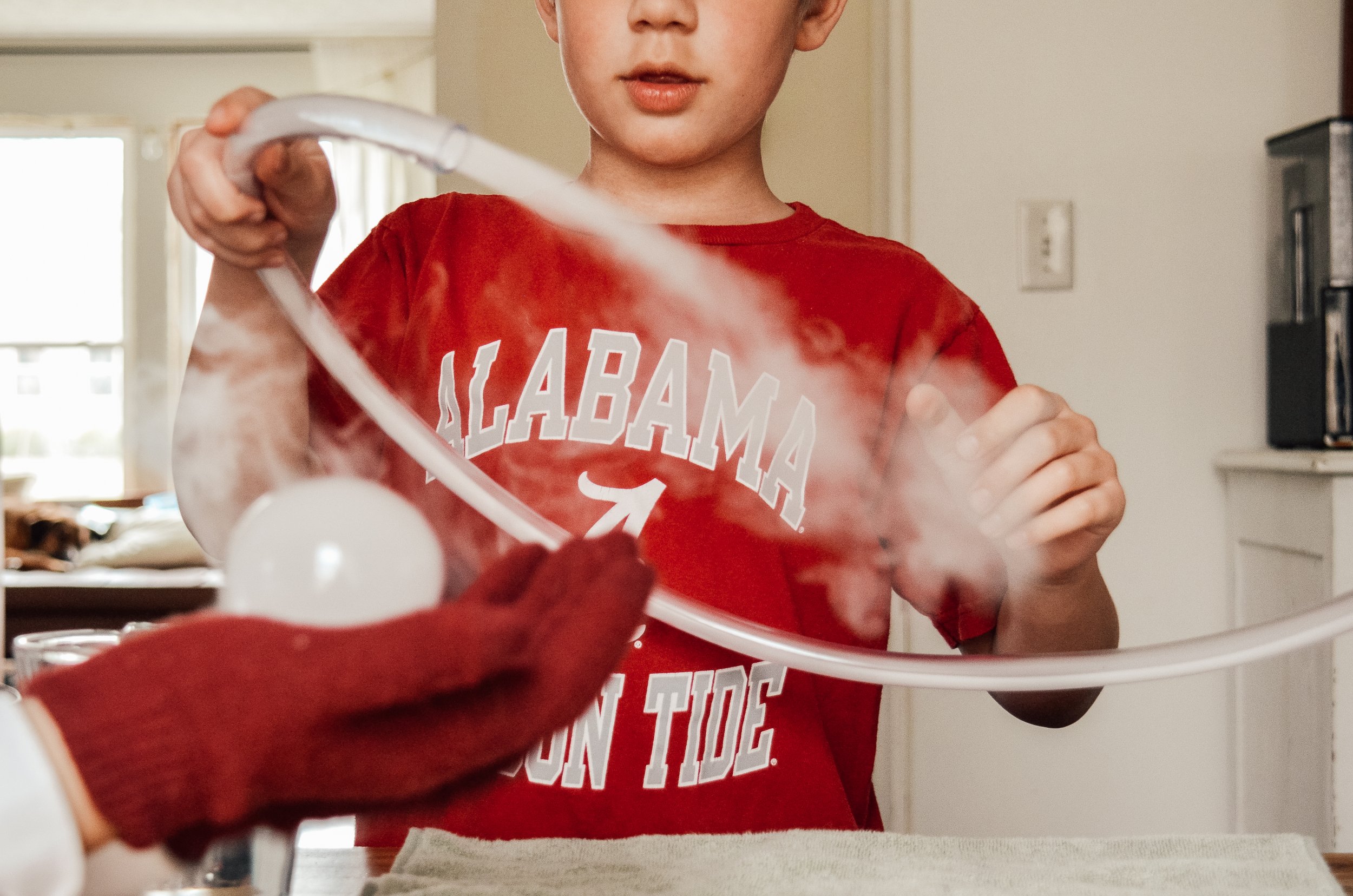

Boo bubbles are bubbles that you can hold, bounce, toss and stack. We made them using dry ice, water and a simple bubble solution. Before I get into the details, let me tell you what dry ice is and give some safety tips for working with it.

Dry ice is created by quickly deep-freezing carbon dioxide. In order to keep it frozen, it must be held at sub-zero temperatures, typically around -110 degrees. Because it is so cold, it is unsafe to touch dry ice with your bare skin; doing so can result in severe burns. ALWAYS wear gloves when handling dry ice. Since dry ice is not made from water, it does not melt. That is, as it warms up, it does not become a liquid. Rather, it reverts to its gaseous form- a process called sublimation (if you look at the jar in the photo above, you can see water in the bottom with bubbles and vapor at the top; the bubbles and vapor are the carbon dioxide formed when dry ice sublimates).

Before we made our bubbles, we talked about the process of sublimation. To observe the difference, we put a piece of dry ice on one plate and a piece of regular ice on another plate and let them sit out while we prepared our experiment. To make our bubble “machine”, we used an empty 1-gallon plastic jar with its lid, some 1/2” clear vinyl tubing, a 1/2” barb x 1/2” adapter fitting, a PVC female adapter, and some plumber’s tape. In the top half of the jar, I cut a hole large enough for the threaded end of the adapter fitting. I wrapped the threaded end with some plumber’s tape and inserted it in the hole, then screwed the female adapter on from inside the jar to hold it in place. I cut a length of the clear tubing- about 4 feet or so- and attached it over the barbed end of the fitting. Then we added a small amount of warm water to the bottom of the jar and created our bubble solution using dish soap and water.

(If you didn’t want to make your own set-up, you could purchase the Boo Bubbles- Dry Ice Smoke Bubbles Experiment kit from Steve Spangler Science.)

When our materials were ready, we went back and looked at the plates. The plate that originally held a piece of regular ice had a small puddle of water. The plate with the dry ice was dry (as an interesting side note, when we set the dry ice on the plate, we could actually hear the process of sublimation happening; when it came in contact with the warm glass of the plate, the dry ice began to vibrate- a result of the extreme temperature difference). Then we dropped some dry ice in the jar, replaced the lid, dipped the free end our tubing in the bubble solution, and watched the magic happen.

The force of the gas exiting the jar through the tubing causes the bubbles to form, and because the vapor is trapped inside the bubble solution, they appear to be filled with smoke. You can drop the bubbles onto a towel-covered surface, where they will sit until the gas dissipates. They are safe to touch bare-handed, however, the oil on our skin causes them to pop, so if you would like to hold the bubbles, you’ll need to wear some cotton gloves. They can be bounced and tossed gently, and even handed from one person to another if passed off carefully.

Playing around and experimenting with these bubbles kept us occupied for a long time. Since the dry ice I bought came in pellet form- pieces about the size of a regular ice cube- it sublimated more quickly than a large chunk and we found that as that happened, the pressure of the gas exiting the jar dropped enough that bubbles would no longer form. Every so often, we just added a few more pellets to the jar. We also found that the temperature of the water in the jar affected the rate at which the ice sublimated and, therefore, the pressure, so we did add more warm water a few times and emptied it and added new water once it got too full (you don’t want the water to get too high or the gas will kid of hang out in the jar above the exit point). We had the most fun making piles of bubbles on the table and also forming a bubble within another bubble. It was also really neat to see how the gas would briefly linger in our hands in the shape of a bubble that popped early.